The parents of a gambling addict who killed himself have said government bodies “do not want to know what killed a perfectly happy and healthy 24-year-old” who was hooked on “products licensed by the state”.

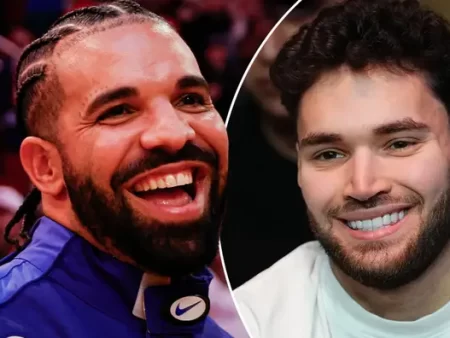

Lawyers for the government and gambling regulator had sought to persuade a coroner that the death of Jack Ritchie from Sheffield could be dealt with in a cursory 15-minute inquest without any discussion of state failures, his parents said.

But on Friday Sheffield’s senior coroner, David Urpeth, decided a full inquest should take place over a fortnight next February.

He will investigate not just how Ritchie came to jump off a building in Hanoi, Vietnam, in November 2017, where he had been teaching English, but how his gambling addiction was treated in the UK and whether he was sufficiently warned of the risks.Advertisement

The inquest will also investigate what medical treatment was available to and received by Ritchie in the UK and how the gambling industry was regulated when he became addicted as a 17-year-old.

But to the frustration of his parents, Charles and Liz Ritchie, it will not explore any possible shortcomings in the government-backed regulator, the Gambling Commission.

The couple have spent the past three years arguing that failures on the part of UK authorities to treat gambling issues had contributed to their son’s death, and campaigning for reform through their charity, Gambling with Lives.

At a socially distanced hearing at Sheffield town hall on Friday, Urpeth insisted an inquest was not the forum for investigating whether the Gambling Commission was doing its job properly. Nor would he explore the adequacy of the 2005 Gambling Act, which came into law before smartphones became ubiquitous, putting temptation in every gambler’s pocket.

But he said he understood the family’s desire for “lessons to be learned” from Ritchie’s death. It “raises very important issues beyond the scope of the inquest” but which the government could decide to explore in a public inquiry, he added.

That was welcomed by Ritchie’s mother, who said she was frustrated the government tried to restrict the inquest.

“It’s so disappointing that the state doesn’t want to know. They are saying they don’t want to know what killed a perfectly happy and healthy 24-year-old who is engaged with products licensed by the state,” said Liz Ritchie. At least the inquest would be a decent length, said her husband: “We were looking at a 15-minute inquest, we’re so much further ahead [now].”

Charles Ritchie told the Guardian earlier this year that he discovered his son’s addiction when he was 18. He promptly took Ritchie into every betting shop in Sheffield, where Ritchie left a photograph and signed a form that would exclude him from placing bets there.

But his addiction simply transferred online and when he arrived in Hull for his first term at university, he blew his student grant in virtual casinos almost immediately. During the Christmas holidays, his parents bought software that blocked his access to gambling sites. But it expired after a year.

On Friday Philip Colvin QC, representing the Gambling Commission, sought to persuade the coroner that it would not be right for the inquest to investigate the link between the gambling industry and suicide.

He made parallels with the alcohol industry, with alcohol the direct cause of more than 7,600 deaths in the UK each year. Such deaths were tragic, he said, “but it couldn’t be suggested that a coroner should look at alcohol pricing, licensing and advertising”.

At an earlier hearing the family’s barrister, Paul Greaney QC, successfully argued that the inquest should engage article 2 of the European convention on human rights, which concerns the right to life – a move typically applied in cases where the state fails to protect the deceased person from risk, such as deaths in police custody.

- In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.

Source for article – The Guardian